- Home

- Lance Hawvermale

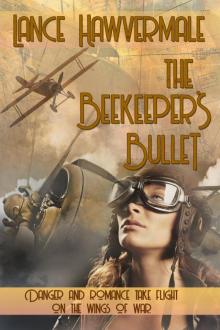

The Beekeeper's Bullet

The Beekeeper's Bullet Read online

Table of Contents

Excerpt

Praise for Lance Hawvermale

The Beekeeper’s Bullet

Copyright

Dedication

Quote

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part Two

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Part Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Epilogue

A word about the author…

Thank you for purchasing

Also available from The Wild Rose Press, Inc.

Something fell from the sky.

A shadow blasted across the truck, briefly barricading the sun. An instant later, a machine of wood and twanging wires flew across the truck’s hood, missing it by the breadth of a hand. Smoke coiled out behind it. The howling contraption flipped in the air, bits of it snapping free even as it dropped, and then it struck a patch of wild forget-me-nots on the side of the road, crushed them, and vanished in the tall grass beyond.

Ellenor torqued the steering wheel to the right and applied brake and clutch, her breath trapped behind her teeth. The truck came to a jarring halt, the two white brood boxes sliding in the back and dislodging a hundred dead bees. Exhaling, she looked from the window in the direction of whatever the hell it was. The war rarely reached this far from the Front; she never fell asleep with the sound of German artillery pounding French hillsides, as so many others did. Other than the occasional supply convoy from the factories in Berlin, Father’s estate and the villages nearby saw no evidence of the blood being hemorrhaged by millions a few dozen miles away. But Ellenor knew, staring from the truck’s dusty window, a part of the war had almost crushed her. Its smoke rose like a serpent from where it waited in the grass.

She opened the door.

Praise for Lance Hawvermale

“Deftly written, [Hawvermale’s] debut is full of appealing characters and moments that sparkle with tenderness.”

~Publisher’s Weekly

~*~

“In a medium that is saturated with go-to potboilers, Lance Hawvermale’s novel shines above it, with vibrant writing and exhilarating flair.”

~Criminal Element

~*~

“[Hawvermale] pushes the envelope, taking the commonplace theme of women’s friendships into dangerous territory and dramatizing what women can do not just to help themselves, but also to bring justice to others.”

~Booklist

~*~

“Hawvermale, balancing suspense with character study, includes enough pauses between the adrenaline-pumping scenes to give his leads the time they need to grow.”

~Kirkus Reviews

~*~

“Hawvermale expertly weaves complex characters and secrets, luring you from one chapter to the next. His prose is at the same time smooth and riveting, and his detective will stay with you even after you’ve closed the back cover.”

~Jean Rabe, author

The Beekeeper’s Bullet

by

Lance Hawvermale

Wind in the Wire, Book 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales, is entirely coincidental.

The Beekeeper’s Bullet

COPYRIGHT © 2019 by Lance Hawvermale

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the author or The Wild Rose Press, Inc. except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

Contact Information: [email protected]

Cover Art by Tina Lynn Stout

The Wild Rose Press, Inc.

PO Box 708

Adams Basin, NY 14410-0708

Visit us at www.thewildrosepress.com

Publishing History

First Vintage Rose Edition, 2019

Print ISBN 978-1-5092-2751-8

Digital ISBN 978-1-5092-2752-5

Wind in the Wire, Book 1

Published in the United States of America

Dedication

To Jerry, Kathy, and Beth

“Once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return.”

~Leonardo da Vinci

Part One

The Flight

Chapter One

She drove down from the mountain, the dead colony in the back of Father’s truck. He wasn’t her real father, of course. But his house was grand and his command of Brahms on the piano even grander, and the only people who didn’t call him Father were those who smoked Turkish tobacco with him in the parlor. And Ellenor Jantz may have been quite brash for a woman of 1917, but her moxie stopped just short of cigars.

The truck bucked through holes in the German countryside, its joints creaking. She tried not to think about the bees.

Instead of bees: mathematics. Her two young charges—Father’s children, ages seven and ten—preferred penmanship and English-language studies over their multiplication tables, but today was Tuesday, and Tuesday meant math. Ellenor herself was no Pythagoras when it came to such things, but she’d been hired over three other quite capable tutors because she was American, she was adept at all things academic, and she could cook käsespätzle almost as well as Father’s late wife. She didn’t fancy numbers as much as she did romantic literature, but wartime work was impossible to find, so she was content to—

Something fell from the sky.

A shadow blasted across the truck, briefly barricading the sun. An instant later, a machine of wood and twanging wires flew across the truck’s hood, missing it by the breadth of a hand. Smoke coiled out behind it. The howling contraption flipped in the air, bits of it snapping free even as it dropped, and then it struck a patch of wild forget-me-nots on the side of the road, crushed them, and vanished in the tall grass beyond.

Ellenor torqued the steering wheel to the right and applied brake and clutch, her breath trapped behind her teeth. The truck came to a jarring halt, the two white brood boxes sliding in the back and dislodging a hundred dead bees. Exhaling, she looked from the window in the direction of whatever the hell it was. The war rarely reached this far from the Front; she never fell asleep with the sound of German artillery pounding French hillsides, as so many others did. Other than the occasional supply convoy from the factories in Berlin, Father’s estate and the villages nearby saw no evidence of the blood being hemorrhaged by millions a few dozen miles away. But Ellenor knew, staring from the truck’s dusty window, a part of the war had almost crushed her. Its smoke rose like a serpent from where it waited in the grass.

She opened the door.

The truck was a 28-horsepower Daimler that Father had purchased five years ago, before the war had bent all civilian industry toward the military effort against Fra

nce and—as the newspapers called them—the Damn Brits. Ellenor Jantz was one of the few women who could operate an automobile. In fact, she’d heard of only one other woman who drove, a stage actress in Stuttgart who was known to advocate for the right to vote, so it was a wonder she’d not yet been run out of town. Ellenor had been born in the New Mexico Territory to an American cattle rancher who’d taught his daughter many things, like how to drive and how to properly groom a horse. And also how to fire a gun.

She took the rifle from the truck as the smoke rose on gray wings from just beyond the pale blue forget-me-nots. Because she’d been inspecting the hives on the hill, she was dressed oddly: canvas trousers tucked into boots a size too large for her, a white top, and a veil-covered pith helmet hanging down her back, its chinstrap tight at her throat. She’d already removed her bulky goatskin gloves. She walked in the direction of the wreckage.

A plane lay crumpled in the German soil. Its wooden fuselage was cracked and bent inward, splinters everywhere. The propeller was little more than a stub, a deep gouge beneath it from where it had screwed itself into the ground. Wires sprang from boards, their ends split and quivering. Fuel burned in small patches in the weeds.

Two hours ago, when finding her bees either dead or absconded, Ellenor had said two words, which she repeated here now as she stood before the ruin that smelled of oil and melting wax: “What happened?”

The plane did not bear the Iron Cross insignia of Germany. Nor did she find any markings of the French enemy. Ellenor’s green eyes scanned the mangled wood until she realized—

“It’s British.”

The blue, white, and red cockade flashed on the remaining tail section as boldly as a target, a defiant ring of color amidst the smoke. Ellenor lifted the rifle, a Mannlicher bolt-action she’d borrowed from Father’s cabinet, the butt smooth against her shoulder. She’d attended a sideshow years ago and witnessed a woman named Annie Oakley shoot tossed coins from the sky, and Miss Oakley’s reputation had nothing to fear from Ellenor Jantz. Still, Ellenor could surprise you at many things. She held the rifle steady as she circled what was left of the plane.

A man lay face down in the dirt.

He wore flyer’s gear: a thick coat to ward off the cold, a leather skullcap, and a silk scarf too flamboyant ever to be permitted for use by the infantry; the scarf was the color of cobalt, an airman’s affectation. One end of it was on fire.

Ellenor leaped forward and crushed her boot against the little flame, obliterating it. She knelt, putting her rifle on the ground, its trigger inches from her knee.

“Hello?”

He made no sound. Ellenor cursed silently to herself. She was terrified of the war and spent most days waiting for the boy from the next village to come with the latest news from the telegraph office. The radio in Father’s study worked only intermittently; French bombs had unraveled too much infrastructure. And yet now the war had suddenly come to her, crashing into the hillside acreage of Father’s estate and ejecting its pilot either dead or injured at her feet.

She put her hands on him, wishing she were still wearing her beekeeping gloves. The leather of his coat was cold but supple, obviously worn on many campaigns. “Can you hear me?”

She rolled him over.

He wore goggles with one smashed-in lens. His cheeks were smooth and bronze and slick with blood from his chin to his left ear. He smelled of gunpowder. The machine gun that had been mounted to his plane was bent and useless a few feet away.

Ellenor checked for a pulse. Is this how the physicians did it? A finger at the throat? She felt something, a steady rhythm—or was it her imagination? “Sir, can you hear me?” She carefully lifted his goggles—

He moved. Muscles firing, eyes flashing open, he shouted and lurched for her, hands grasping. She pulled back just in time, finding the rifle precisely where she intended it to be, pointing it at him even as she sprang to her feet.

He was feral. Feral and wounded and lost on the wrong side of the Front. Instinctively he reacted to save himself, snarling as he lunged straight at her with startling velocity.

Ellenor had never shot anyone before. Indeed, she’d never fired a weapon at anything other than the coyotes that used to torment her mother’s hens. She’d brought the twenty-year-old Mannlicher from Father’s study because he insisted she not go into the wilderness unarmed during times of war, even though the trenches were miles away. She told him it was unnecessary, but he was a man who insisted things and then meant those things, so she’d dutifully loaded the weapon and stowed it in the truck.

The pilot closed the small gap between them. Ellenor reflexively jerked the trigger. The eight-millimeter bullet blasted from the barrel.

He caught it.

The man whipped his hand in front of his face at the exact moment she fired. He snapped his fist around the incoming slug in midair, and it bored a hole through his palm and out the back of his hand. But he managed to alter its trajectory just enough that the bullet whispered an inch from his head, sparing his life.

Ellenor gasped. The airman fell, moaning, clutching his new wound to his chest.

She took several steps backward, working the rifle’s bolt to chamber another round, stunned by what she’d nearly done. “Stop it!” she yelled at him, the rifle bobbing up and down in her panicked grip. She’d almost killed him, would have killed him had he not gotten lucky. She felt suddenly like vomiting into the grass. “Stay there or I’ll kill you.”

He must have believed her. More likely, he was startled to hear her speaking English. Either way, he rolled onto his side and then held still, injured hand pinched in his armpit, squinting up at her.

She fought to regain her breath. She’d come half a second from being a murderer. And the damn hat’s chinstrap was choking her to death, but she couldn’t risk taking a hand from the rifle. “I said not to move.”

He coughed. “Does it bloody well look like I’m moving?”

“Shut up.”

He said nothing else. He laid his head on the ground, wincing, apparently becoming aware of all his injuries at once. He’d survived the crash by chance alone, but his body had paid for his good fortune. His bright blue scarf looked absurd against the blood and the dirt.

Ellenor’s body finally relaxed. The tension still forced her cheek against the rifle’s stock, but her heart came back down to earth. In a matter of minutes, she’d gone from lamenting two dead beehives to almost killing a foreign soldier. The day had begun in such an ordinary way, with mathematics lessons followed by English-language practice followed by a war report from the boy on the bicycle. Father had paid him with a pair of red apples and sent him on his way.

And now this. When she was certain the man wasn’t about to launch another assault, she slowly began to move toward the truck, never letting the barrel’s iron sights leave her target. The idea of trying to tie him up and haul him to the authorities was outlandish, so she’d report the matter to Father and let him—

“Don’t leave me here,” the pilot said.

She stopped. Yes, he was British. His accent said as much. And Ellenor, being American, should have been sympathetic—the two of them bound by the King’s English and all—but her home country had only recently decided to wade uncertainly into the war, and so she felt no particular fealty to one side or the other. All wars were run by idiotic men in hats; they scrapped over land and religion and sent boys half their age to die in tangles of barbed wire or gas-filled holes. They were all the same.

“Please.”

She lifted her cheek from the rifle’s smooth wood. The British pilot looked up at her, blood ringing one blue-gray eye. He was doomed. The Front was too far. Whatever aerodrome served as his base somewhere in the French countryside might as well have been in outer space. He would not make it out of Germany, not torn half to bits like this. The Polizei would arrest him or the army would imprison him. Or perhaps he’d bleed to death here among the undeserving forget-me-nots. Flyers died violent d

eaths, their airplanes too ridiculous to remain for long in the sky.

He said something too softly for her to hear.

She looked down the dirt track that lay like a ribbon on the hillside. Father’s house was still another mile, at least. A hundred yards from where she stood with her rifle, a deer nibbled on clover, unaware of the war, unaware of Ellenor and the decision she had to make.

She turned her attention back to the man she’d almost killed. “What did you say?”

He closed his eyes. “I have to…to find her.”

“Find whom?”

He didn’t say. The pain clubbed him, bound him, and dragged him down to darkness.

She lowered the rifle and sighed. She glanced back toward the deer, perhaps for moral support, but the animal had fled without sound.

Chapter Two

She used a rope and pulley to drag him into the truck.

The simple block-and-tackle rig was something Father had suggested for helping Ellenor manhandle the heavy hives. Each box, when filled with ten frames of honey to be harvested, could weigh as much as eighty pounds. Ellenor depended on physics to assist her, and eventually she winched the foreigner into position just behind the vehicle’s cab. He slept and bled.

She unwound the blue scarf from his neck, intending to wrap the hand she’d shot, but the hole was nasty; it leaked slowly, continuously. Pressure would help, but the man was unconscious and not able to assist in his own first aid.

“Why bother?” Ellenor asked herself. Normally she’d talk with the bees, a delightful chorus of eager girls who reaped nectar and pollen from German wildflowers and ferried them into their homes. But she had no bees other than the dead, their corpses awaiting closer inspection in Father’s barn. Instead, she talked to herself.

“Damned if I know.”

The bleeding had to be stopped. Ellenor took the nearest hive box and removed the frames, wax-filled forms on which the bees constructed their hexagonal treasure boxes. Using a flat-bladed tool, she scraped the edges of the frames, building up a sticky wad of propolis, which was the beekeeper’s term for processed tree sap. Bees used it for mortar and sealant. Ellenor could think of nothing more appropriate for her task.

The Beekeeper's Bullet

The Beekeeper's Bullet Face Blind

Face Blind